By Johnny Vedmore on twitter

Part 1:

Schwab Family Values

On the morning of 11 September 2001, Klaus Schwab sat having breakfast in the Park East Synagogue in New York City with Rabbi Arthur Schneier, former Vice President for the World Jewish Congress and close associate of the Bronfman and Lauder families. Together, the two men watched one of the most impactful events of the next twenty years unfold as planes struck the World Trade Center buildings. Now, two decades on, Klaus Schwab again sits in a front row seat of yet another generation-defining moment in modern human history.

Always seeming to have a front row seat when tragedy approaches, Schwab’s proximity to world-altering events likely owes to his being one of the most well-connected men on Earth. As the driving force behind the World Economic Forum, “the international organization for public-private cooperation,” Schwab has courted heads of state, leading business executives, and the elite of academic and scientific circles into the Davos fold for over 50 years. More recently, he has also courted the ire of many due to his more recent role as the frontman of the Great Reset, a sweeping effort to remake civilization globally for the express benefit of the elite of the World Economic Forum and their allies.

Schwab, during the Forum’s annual meeting in January 2021, stressed that the building of trust would be integral to the success of the Great Reset, signalling a subsequent expansion of the initiative’s already massive public relations campaign. Though Schwab called for the building of trust through unspecified “progress,” trust is normally facilitated through transparency. Perhaps that is why so many have declined to trust Mr. Schwab and his motives, as so little is known about the man’s history and background prior to his founding of the World Economic Forum in the early 1970s.

Like many prominent frontmen for elite-sponsored agendas, the online record of Schwab has been well-sanitized, making it difficult to come across information on his early history as well as information on his family. Yet, having been born in Ravensburg, Germany in 1938, many have speculated in recent months that Schwab’s family may have had some tie to Axis war efforts, ties that, if exposed, could threaten the reputation of the World Economic Forum and bring unwanted scrutiny to its professed missions and motives.

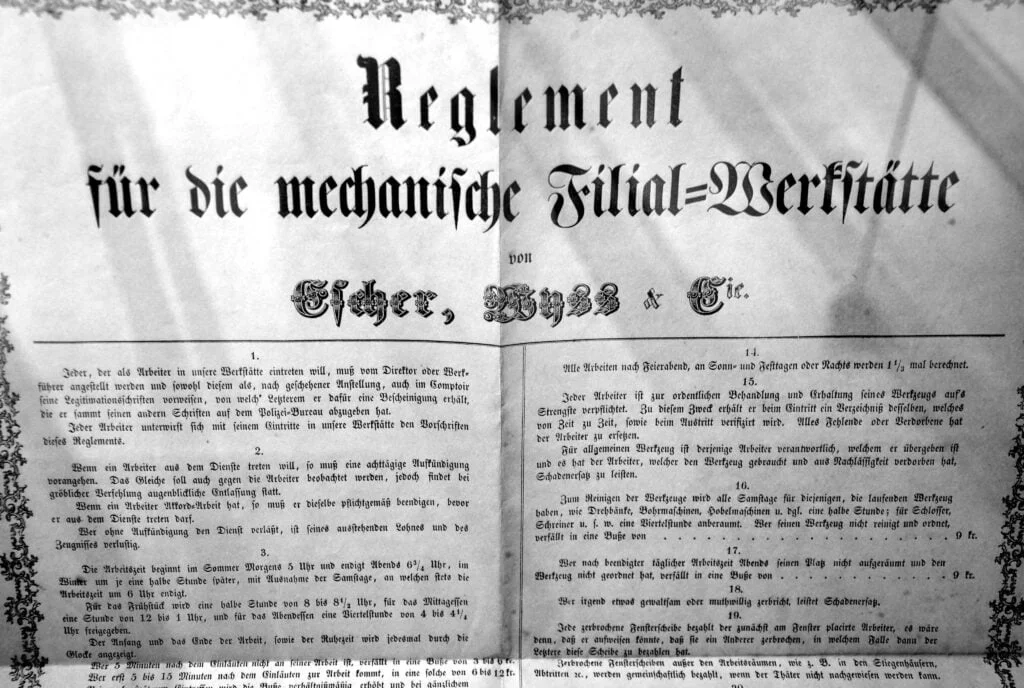

In this Unlimited Hangout investigation, the past that Klaus Schwab has worked to hide is explored in detail, revealing the involvement of the Schwab family, not only in the Nazi quest for an atomic bomb, but apartheid South Africa’s illegal nuclear programme. Especially revealing is the history of Klaus’ father, Eugen Schwab, who led the Nazi-supported German branch of a Swiss engineering firm into the war as a prominent military contractor. That company, Escher-Wyss, would use slave labor to produce machinery critical to the Nazi war effort as well as the Nazi’s effort to produce heavy water for its nuclear program. Years later, at the same company, a young Klaus Schwab served on the board of directors when the decision was made to furnish the racist apartheid regime of South Africa with the necessary equipment to further its quest to become a nuclear power.

With the World Economic Forum now a prominent advocate for nuclear non-proliferation and “clean” nuclear energy, Klaus Schwab’s past makes him a poor spokesperson for his professed agenda for the present and the future. Yet, digging even deeper into his activities, it becomes clear that Schwab’s real role has long been to “shape global, regional and industry agendas” of the present in order to ensure the continuity of larger, much older agendas that came into disrepute after World War II, not just nuclear technology, but also eugenics-influenced population control policies.

A Swabian Story

On 10 July 1870, Klaus Schwab’s grandfather Jakob Wilhelm Gottfried Schwab, referred to later as simply Gottfried, was born in a Germany at war with its French neighbours. Karlsruhe, the town where Gottfried Schwab was born, was located in the Grand Duchy of Baden, ruled in 1870 by the 43 year old Grand Duke of Baden, Frederick I. The following year, the aforementioned Duke would be present at the proclamation of the German Empire which took place in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. He was the only son-in-law of the incumbent Emperor Wilhelm I and, as Frederick I, was one of the reigning sovereigns of Germany. By the time Gottfried Schwab turned 18 years old, Germany would see Wilhelm II take the throne upon the death of his father, Frederick III.

In 1893, a 23 year old Gottfried Schwab would officially depart from Germany giving up his German citizenship and leaving Karlsruhe in order to emigrate to Switzerland. At the time, his occupation was noted as being that of a simple baker. Here, Gottfried would meet Marie Lappert who was from Kirchberg near Bern, Switzerland and who was five years his junior. They would marry in Roggwil, Bern, on 27 May 1898 and the following year, on 27 April 1899, their child Eugen Schwab was born. At the time of his birth, Gottfried Schwab had moved up in the world, having become a Machine Engineer. When Eugen was around one year old, Gottfried and Marie Schwab decided to return to live in Karlsruhe and Gottfried reapplied for German citizenship again.

Eugen Schwab would follow in the footsteps of his father and also become a Machine Engineer and in future years, he would advise his children to do the same. Eugen Schwab would eventually begin working at a factory in a town in Upper Swabia in Southern Germany, capital of the district of Ravensburg, Baden-Württemberg.

The factory where he would forge his career was the German branch of a Swiss company named Escher Wyss. Switzerland had many long standing economic ties to the Ravensburg area, with Swiss traders in the early 19th century bringing in yarn and weaving products. In the same period, Ravensburg delivered grain to Rorschach until 1870, alongside breeding animals and various cheeses, deep within the Swiss Alps. Between 1809 and 1837, there were 375 Swiss people living in Ravensburg, though the Swiss population had dropped to 133 by 1910.

In the 1830s, skilled Swiss workers set up a cotton factory with an incorporated bleaching and finishing plant owned and maintained by the Erpf brothers. The Ravensburg horse market, created in around 1840, also attracted many people from Switzerland, especially after the 1847 opening of the railway line from Ravensburg to Friedrichshafen, a town situated on nearby Lake Constance on the borderlands of Switzerland and Germany.

Rorsach grain traders would make regular visits to the Ravensburger Kornhaus and eventually this cross-border cooperation and trade also led to a branch of the Zurich machine factory, Escher-Wyss & Cie, opening in the city. This feat was made plausible once a train line connecting the Swiss to the German route network was completed between 1850 and 1853. The factory was set up by Walter Zuppinger between 1856 to 1859 and would begin production in 1860. In 1861, we can see the first official patent of the manufacturers Escher-Wyss in Ravensburg of “peculiar facilities on mechanical looms for ribbon weaving”. At this time, the Ravensburg branch of Escher Wyss would be directed by Walter Zuppinger, and would be where he developed his tangential turbine and where he gained a number of additional patents. In 1870, Zuppinger along with others would also founded a paper mill works in Baienfurt close to Ravensburg. He retired in 1875 and devoted all his energies to the further advance of turbines.

At the turn of the new century, Escher-Wyss had put the ribbon weaving to one side and begun to concentrate on much bigger projects like the production of large industrial turbines and, in 1907, they sought an “approval and concession procedure” for the construction of a hydropower plant near Dogern am Rhein, which was reported in a Basel brochure from 1925.

By 1920, Escher-Wyss found themselves embroiled in serious financial difficulties. The treaty of Versailles had restricted the military and economic growth of Germany following the Great War, and the Swiss Company found the downturn in neighbouring national civil engineering projects too much to bear. The parent branch of Escher-Wyss was located in Zurich and dated back to 1805 and the company, which still benefited from a good reputation and a history lasting more than a century, was deemed too important to lose. In December 1920, a reorganization was carried out by writing down the share capital from 11.5 to 4.015 million French Francs and which was later increased again to 5.515 million Swiss Francs. By the end of the financial year of 1931, Escher-Wyss was still losing money.

Yet, the plucky company continued to deliver large scale civil engineering contracts throughout the 1920s as noted in the official correspondence written in 1924 from Wilhelm III Prince of Urach to the company Escher-Wyss and to the asset manager of the House of Urach, accountant Julius Heller. This document discusses the “General Terms and Conditions of the Association of German Water Turbine Manufacturers for the Delivery of Machines and Other Equipment for Hydropower Plants”. This is also confirmed in a brochure on the “Conditions of the Association of German Water Turbine Manufacturers for the Installation of Turbines and Machine Parts within the German Reich”, printed on March 20, 1923 in an advertising brochure from Escher-Wyss for a universal oil pressure regulator.

After the Great Depression in the early 1930s had laid waste to the global economy, Escher-Wyss announced, “as the catastrophic development of the economic situation in connection with the currency declines; The company [Escher-Wyss] is temporarily unable to continue its current liabilities in various customer countries.” The company also revealed that they would apply for a court deferral to the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Nachrichten, which reported on 1 December 1931 that, “the company Escher-Wyss has been granted a stay of bankruptcy until the end of March 1932 and, acting as curator in Switzerland, a trust company has been appointed.” The article stated optimistically that, “there should be a prospect of continuing operations.” In 1931, Escher-Wyss employed around 1,300 non-contracted workers and 550 salaried employees.

By the mid-1930s, Escher-Wyss had again found itself in financial trouble. In order to rescue the company this time, a consortium was brought on board to save the ailing engineering firm. The consortium was partly formed by the Federal Bank of Switzerland (which was coincidently headed by a Max Schwab, who is of no relation to Klaus Schwab) and further restructuring took place. In 1938, it was announced that an engineer at the firm, Colonel Jacob Schmidheiny would become the new President of the Board of Directors at Escher-Wyss. Soon after the outbreak of war in 1939, Schmidheiny was quoted as saying, “The outbreak of war does not necessarily mean unemployment for the machine industry in a neutral country, on the contrary.” Escher-Wyss, and its new management, were apparently looking forward to profiting off the war, paving the way for their transformation into a major Nazi military contractor.

A Brief History of Jewish Persecution in Ravensburg

When Adolf Hitler came to power, many things changed in Germany, and the story of the Jewish population of Ravensburg during that era is a sad one to tell. Yet, it was hardly the first time that anti-Semitism had first been recorded as having reared its ugly head in the region.

In the Middle Ages, a synagogue, mentioned as far back as 1345 was located at the centre of Ravensburg, serving a small Jewish community which can be traced from 1330 to 1429. At the end of 1429 and through 1430, the Jews of Ravensburg were targeted and a horrific massacre ensued. In the nearby settlements of Lindau, Überlingen, Buchhorn (later renamed Friedrichshafen), Meersburg and Konstanz, there were mass arrests of Jewish residents. The Jews of Lindau were burnt alive during the 1429/1430 Ravensburg blood libel, in which members of the Jewish community were accused of ritually sacrificing babies. In August 1430, in Überlingen, the Jewish community was forced to convert, 11 of them did so and the 12 who refused were killed. The massacres which took place in Lindau, Überlingen and Ravensburg happened with the direct approval of the ruling King Sigmund and any remaining Jews were soon expelled from the region.

Ravensburg had this ban confirmed by Emperor Ferdinand I in 1559 and it was upheld, for example, in an 1804 instruction issued for the city guard, which read: “Since the Jews are not allowed to engage in any trade or business here, no one else is allowed to enter the city by post or by carriage, The rest, however, if they have not received a permit for a longer or shorter stay from the police office, are to be removed from the city by the police station.”

Not until the 19th century were Jews able to settle legally in Ravensburg again and, even by then, their number remained so small that a synagogue was not rebuilt. In 1858, there were only 3 Jews recorded in Ravensburg and, in 1895, this number peaked at 57. From the turn of the century until 1933, the numbers of Jews living in Ravensburg had steadily decreased until the community was only made up of 23 people.

By the start of the 1930s, there were seven main Jewish families living in Ravensburg, including the Adler, Erlanger, Harburger, Herrmann, Landauer, Rose and Sondermann families. After the National Socialists seized power, some of the Ravensburg Jews were initially forced to emigrate, while others would later be murdered in Nazi concentration camps. Leading up to World War II, there were many public displays of hatred towards the small community of Jews in and around Ravensburg.

As early as March 13, 1933, about three weeks before the nationwide Nazi boycott of all Jewish shops in Germany, SA guards posted themselves in front of two of the five Jewish shops in Ravensburg and tried to prevent potential buyers from entering, putting up signs on one shop stating “Wohlwert closed until Aryanization”. Wohlwert’s would soon become “Aryanised” and would be the only Jewish-owned shop to survive the Nazi pogrom. The other owners of the four large Jewish department stores in Ravensburg; Knopf; Merkur; Landauer and Wallersteiner were all forced to sell their properties to non-Jewish merchants between 1935 and 1938. During this period, many of the Ravensburg Jews were able to flee abroad before the worst of the National Socialist persecution began. While at least eight died violently, it was reported that three Jewish citizens who lived in Ravensburg survived because of their “Aryan” spouses. Some of the Jews who were arrested in Ravensburg during Kristallnacht were forced to march through the streets of Baden-Baden under SS guard supervision the following day and were later deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Horrific Nazi crimes against humanity took place in Ravensburg. On 1 January 1934, the “Law for the Prevention of Hereditary Diseases” came into force in Nazi Germany, meaning people with diagnosed illnesses such as dementia, schizophrenia, epilepsy, hereditary deafness, and various other mental disorders, could be legally forcibly sterilised. In the Ravensburg City Hospital, today called Heilig-Geist Hospital, forced sterilisations were carried out beginning in April 1934. By 1936, sterilisation was the most performed medical procedure in the municipal hospital.

In the pre-war years of the 1930s leading up to the German annexation of Poland, Ravensburg’s Escher-Wyss factory, now managed directly by Klaus Schwab’s father, Eugen Schwab, continued to be the biggest employer in Ravensburg. Not only was the factory a major employer in the town, but Hitler’s own Nazi party awarded the Escher-Wyss Ravensburg branch the title of “National Socialist Model Company” while Schwab was at the helm. The Nazis were potentially wooing the Swiss company for cooperation in the coming war, and their advances were eventually reciprocated.

Escher-Wyss Ravensburg and the War

Ravensburg was an anomaly in wartime Germany, as it was never targeted by any Allied airstrikes. The presence of the Red Cross, and a rumoured agreement with various companies including Escher-Wyss, saw the allied forces publicly agree to not target the Southern German town. It was not classified as a significant military target throughout the war and, for that reason, the town still maintains many of its original features. However, much darker things were afoot in Ravensburg once the war began.

Eugen Schwab continued to manage the “National Socialist Model Company” for Escher-Wyss, and the Swiss company would aid the Nazi Wermacht produce significant weapons of war as well as more basic armaments. The Escher-Wyss company was a leader in large turbine technology for hydroelectric dams and power plants, but they also manufactured parts for German fighter planes. They were also intimately involved in much more sinister projects happening behind the scenes which, if completed, could have changed the outcome of World War II.

Western military intelligence were already aware of Escher-Wyss’ complicity and collaboration with the Nazis. There are records available from western military intelligence at the time, specifically Record Group 226 (RG 226) from the data compiled by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which shows the Allied forces were aware of some of the Escher-Wyss’ business dealings with the Nazis.

Within RG 226, there are three specific mentions of Escher-Wyss including:

- File number 47178 which reads: Escher-Wyss of Switzerland is working on a large order for Germany. Flame-throwers are despatched from Switzerland under the name Brennstoffbehaelter. Dated Sept. 1944.

- File number 41589 showed that the Swiss were allowing German exports to be stored in their country, a supposedly neutral nation during World War II. The entry reads: Business relations between Empresa Nacional Calvo Sotelo (ENCASO), Escher Wyss, and Mineral Celbau Gesellschaft. 1 p. July 1944; see also L 42627 Report on collaboration between the Spanish Empresa Nacional Calvo Sotelo and the German Rheinmetall Borsig, on German exports stored in Switzerland. 1 p. August 1944.

- File number 72654 claimed that: Hungary’s bauxite was formerly sent to Germany and Switzerland for refining. Then a government syndicate built an aluminium plant at Dunaalmas on the borders of Hungary. Electric power was provided; Hungary contributed coal mines, and equipment was ordered from the Swiss firm Escher-Wyss. Production began in 1941. 2 pp. May 1944.

Yet, Escher-Wyss were leaders in one blossoming field in particular, the creation of new turbine technology. The company had engineered a 14,500 HP turbine for the Norsk Hydro industrial facility’s strategically important hydroelectric plant at Vemork, near Rjukan in Norway. The Norsk Hydro plant, part powered by Escher Wyss, was the only industrial plant under Nazi control capable of producing heavy water, an ingredient essential for making plutonium for the Nazi atomic bomb program. The Germans had put all possible resources behind the production of heavy water, but the Allied forces were aware of the potentially game-changing tech advances by the increasingly desperate Nazis.

During 1942 and 1943, the hydro plant was the target of partially successful British Commando and Norwegian Resistance raids, although heavy water production continued. The Allied forces would drop more than 400 bombs on the plant, which barely affected the operations at the sprawling facility. In 1944, German ships attempted to transport heavy water back to Germany, but the Norwegian Resistance were able to sink the ship carrying the payload. With help from Escher-Wyss, the Nazis were almost able to change the tides of war and bring about an Axis victory.

Back in the Escher-Wyss factory in Ravensburg, Eugen Schwab had been busy putting forced labourers to work at his model Nazi company. During the years of World War II, nearly 3,600 forced labourers worked in Ravensburg, including at Escher Wyss. According to the city archivist in Ravensburg, Andrea Schmuder, the Escher-Wyss machine factory in Ravensburg employed between 198 and 203 civil workers and POWs during the war. Karl Schweizer, a local Lindau historian, states that Escher-Wyss maintained a small special camp for forced labourers on the factory premises.

The use of masses of forced labourers in Ravensburg made it necessary to setup one of the largest recorded Nazi forced labour camps in the workshop of a former carpenter’s at Ziegelstrasse 16. At one time, the camp in question accommodated 125 French prisoners of war who were later redistributed to other camps in 1942. The French workers were replaced by 150 Russian prisoners of war who, it was rumoured, were treated the worst out of all the POWs. One such prisoner was Zina Jakuschewa, whose work card and work book are held by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Those documents identify her as a non-Jewish forced labourer assigned to Ravensburg, Germany, during 1943 and 1944.

Eugen Schwab would dutifully maintain the status quo during the war years. After all, with young Klaus Martin Schwab having been born in 1938 and his brother Urs Reiner Schwab born a few years later, Eugen would have wanted to keep his children out of harm’s way.

Klaus Martin Schwab – International Man of Mystery

Born on 30 March 1938 in Ravensburg, Germany, Klaus Schwab was the eldest child in a normal nuclear family. Between 1945 and 1947, Klaus attended primary school in Au, Germany. Klaus Schwab recalls in a 2006 interview with the Irish Times that:”After the war, I chaired the Franco-German regional youth association. My heroes were Adenauer, De Gasperi and De Gaulle.”

Klaus Schwab and his younger brother, Urs Reiner Schwab, were both to follow in the footsteps of their grandfather, Gottfried, and their father, Eugen, and would both initially train as machine engineers. Klaus’s father had told the young Schwab that, if he wanted to make an impact on the world, then he should train as a Machine Engineer. This would only be the beginning of Schwab’s University credentials.

Klaus would begin studying his plethora of degrees at Spohn-Gymnasium Ravensburg between 1949 and 1957, eventually graduating from the Humanistisches Gymnasium in Ravensburg. Between 1958 and 1962, Klaus began working with various engineering companies and, in 1962, Klaus completed his mechanical engineering studies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich with an engineering diploma. The following year, he also completed an economics course at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. From 1963 until 1966, Klaus worked as Assistant to the Director-General of the German Machine-building Association (VDMA), Frankfurt.

In 1965, Klaus was also working on his doctorate from the ETH Zurich, writing his dissertation on: “The longer-term export credit as a business problem in mechanical engineering”. Then, in 1966, he received his Doctorate in Engineering from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich. At this time, Klaus’s father, Eugen Schwab, was swimming in bigger circles than he had previously swam. After being a well known personality in Ravensburg as the Managing Director of the Escher-Wyss factory from before the war, Eugen would eventually be elected as President of the Ravensburg Chamber of Commerce. In 1966, during the founding of the German committee for Splügen railway tunnel, Eugen Schwab defined the founding of the German committee as a project “that creates a better and faster connection for large circles in our increasingly converging Europe and thus offers new opportunities for cultural, economic and social development”.

In 1967, Klaus Schwab gained a Doctorate in Economics from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland as well as a Master of Public Administration qualification from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard in the United States. While at Harvard, Schwab was taught by Henry Kissinger, who he would later say were among the top 3-4 figures who had most influenced his thinking over the course of his entire life.

In the previously mentioned Irish Times article of 2006, Klaus talks about that period as being very important to the formation of his present idealogical thinking, stating: “Years later, when I came back from the US after my studies at Harvard, there were two events that had a decisive triggering event on me. The first was a book by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, The American Challenge – which said Europe would lose out against the US because of Europe’s inferior management methods. The other event was – and this is relevant to Ireland – the Europe of the six became the Europe of the nine.” These two events would help shape Klaus Schwab into a man who wanted to change the way people went about their business.

That same year, Klaus’s younger brother Urs Reiner Schwab graduated from ETH Zurich as a mechanical engineer, and Klaus Schwab went to work for his father’s old company, Escher-Wyss, soon to become Sulzer Escher-Wyss AG, Zurich, as Assistant to the Chairman to aid in the reorganisation of the merging companies. This leads us towards Klaus’s nuclear connections.

The rise of a technocrat

Sulzer, a Swiss company whose origins date back to 1834, had first risen to prominence after starting to build compressors in 1906. By 1914, the family-run firm had become part of “three joint-stock companies,” one of which was the official holding company. In the 1930s, Sulzer’s profits would suffer during the Great Depression and, like many businesses at the time, faced disruption and industrial actions from their workers.

World War II may not have affected Switzerland as much as her neighbours, but the economic boom that was to follow led to Sulzer growing in power and market dominance. In 1966, just before the arrival of Klaus Schwab at Escher-Wyss, the Swiss turbine manufacturers signed a cooperation agreement with the Sulzer brothers in Winterthur. Sulzer and Escher-Wyss would begin to merge in 1966, when Sulzer purchased 53% of the company shares. Escher-Wyss would officially become Sulzer Escher-Wyss AG in 1969 when the last of the shares were acquired by the Sulzer brothers.

Once the merger had started, Escher-Wyss would begin to be restructured and two of the existing Board Members would be the first to find their service to Escher-Wyss coming to an end. Dr. H. Schindler and W. Stoffel would resign from the Board of Directors now headed by Georg Sulzer and Alfred Schaffner. Dr. Schindler had been a member of the Escher-Wyss Board of Directors for 28 years and had worked alongside Eugen Schwab throughout much of his service. Peter Schmidheiny would later take over as Chairman of the Board of Directors of Escher-Wyss, continuing the Schmidheiny family rule over the company’s executives.

During the restructuring process, it was decided that Escher-Wyss and Sulzer would concentrate on separate areas of machine engineering with the Escher-Wyss factories primarily work on hydraulic power plant construction, including turbines, storage pumps, reversing machines, closing devices and pipelines, as well as steam turbines, turbo compressors, evaporation systems, centrifuges and machines for the paper and pulp industry. Sulzer would concentrate on the refrigeration industry as well as steam boiler construction and gas turbines.

On 1 January 1968, the freshly reorganised Sulzer Escher-Wyss AG was rolled out publicly and the company had become streamlined, a move deemed necessary because of several large acquisitions. This included a close collaboration with Brown Boveri, a group of Swiss electric engineering companies who had also worked for the Nazis, supplying the Germans with some of their U-boat technology used during World War II. Brown Boveri was also described as “defence-related electrical contractors” and would find the conditions of the Cold War arms race to be beneficial to their business.

The merger and reorganisation of these Swiss mechanical engineering giants saw their collaboration pay off in unique ways. During the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, Sulzer and Escher-Wyss used 8 refrigeration compressors to create tonnes of artificial ice. In 1969, the two firms combined to help in the building of a new passenger ship named “Hamburg”, the first ship in the world to be fully air-conditioned thanks to the Sulzer Escher-Wyss combination.

In 1967, Klaus Schwab officially burst onto the scene of the Swiss business community and took a lead in the merger between Sulzer and Escher-Wyss, as well as forming profitable alliances with Brown Boveri and others. In December 1967, Klaus would speak at a Zurich event to the top Swiss machine engineering organisations; the Employers Association of Swiss Machine and Metal Manufacturers and the Association of Swiss Machine Manufacturers.

In his talk, he would correctly predict the importance of incorporating computers into modern Swiss machine engineering, stating that:

“In 1971, products that are not even on the market today are likely to account for up to a quarter of sales. This requires companies to systematically research possible developments and identify gaps in the market. Today, 18 of the 20 largest companies in our machine industry have planning departments that are entrusted with such tasks. Of course, everyone has to make use of the latest technological advances, and the computer is one of them. The many small and medium-sized companies in our machine industry take the path of cooperation or use the services of special data processing service providers.”

Computers and data were obviously seen as important to the future, according to Schwab, and this was further projected in the reorganisation of Sulzer Escher-Wyss during their merger. Sulzer’s modern website reflects this noteworthy change in direction, stating that, in 1968: “Material technology activities are intensified [by Sulzer] and form the basis for medical technology products. The fundamental change from a machine-building company to a technology corporation starts to become apparent.”

Klaus Schwab was helping to turn Sulzer Escher-Wyss into something more than just a machine building giant, he was transforming them into a technology corporation driving at high speed into a hi-tech future. It should also be noted that Sulzer Escher-Wyss changed another focus of their business to help them “form the basis for medical technology products,” an area not previously mentioned as a target industry for Sulzer and/or Escher-Wyss.

But technological advancement wasn’t the only upgrade Klaus Schwab wanted to introduce at Sulzer Escher-Wyss, he also wanted to change how the company thought about their business managerial style. Schwab and his close associates were pushing an entirely new business philosophy which would allow “all employees to accept the imperatives of motivation and to ensure at home a sense of flexibility and manoeuvrability.”

It is here in the late 1960s where we see Klaus begin to emerge as a more public figure. At this time, the Sulzer Escher-Wyss company also became more interested in engaging with the press than ever before. In January 1969, the Swiss giants setup a public advisory session entitled the “Press Day of the Machine Industry“, which mainly concerned questions on company management. During the event, Schwab would state that companies using authoritarian styles of business management are “unable to fully activate the ‘human capital’”, an argument he would use on many separate occasions during the late 1960s.

Plutonium and Pretoria

Escher-Wyss were pioneers in some of the most important tech in power generation. As the US Department of Energy points out in their paper on Supercritical CO2 Brayton Cycle Development (CBC), a device used in hydro and nuclear power plants, “Escher-Wyss was the first company known to develop the turbomachinery for CBC systems starting in 1939.” Going on to state that 24 systems were built, “with Escher-Wyss designing the power conversion cycles and building the turbomachinery for all but 3”. By 1966, just before the entrance of Schwab into Escher-Wyss and the start of the Sulzer merger, the Escher-Wyss helium compressor was designed for the La Fleur Corporation and continued the evolution of the Brayton Cycle Development. This technology was still of importance to the arms industry by 1986, with nuclear powered drones being equipped with a helium-cooled Brayton cycle nuclear reactor.

Escher-Wyss had been involved with manufacturing and installing nuclear technology at least as early as 1962, as shown by this patent for a “heat exchange arrangement for a nuclear power plant” and this patent from 1966 for a “nuclear reactor gas-turbine plant with emergency cooling”. After Schwab left Sulzer Escher-Wyss, Sulzer would also help to develop special turbocompressors for uranium enrichment to yield reactor fuels.

When Klaus Schwab joined Sulzer Escher-Wyss in 1967 and started the reorganisation of the company to be a technology corporation, the involvement of Sulzer Escher-Wyss in the darker aspects of the global nuclear arms race became immediately more pronounced. Before Klaus became involved, Escher-Wyss had often concentrated on helping design and build parts for civilian uses of nuclear technology, e.g. nuclear power generation. Yet, with the arrival of the eager Mr. Schwab also came the company’s participation in the illegal proliferation of nuclear weapons technology. By 1969, the incorporation of Escher Wyss into Sulzer was fully completed and they would be rebranded into Sulzer AG, dropping the historic name Escher-Wyss from their name.

It was eventually revealed, thanks to a review and report carried out by the Swiss authorities and a man named Peter Hug, that Sulzer Escher-Wyss began secretly procuring and building key parts for nuclear weapons during the 1960s. The company, while Schwab was on the board, also began playing a critical key role in the development of South Africa’s illegal nuclear weapons programme during the darkest years of the apartheid regime. Klaus Schwab was a leading figure in the founding of a company culture which helped Pretoria build six nuclear weapons and partially assemble a seventh.

In the report, Peter Hug outlined how Sulzer Escher Wyss AG (referred to post-merger as just Sulzer AG) had supplied vital components to the South African government and found evidence of Germany’s role in supporting the racist regime, also revealing that the Swiss government “was aware of illegal deals but ‘tolerated them in silence’ while supporting some of them actively or criticised them only half-heartedly”. Hug’s report was eventually finalised in a work entitled: “Switzerland and South Africa 1948-1994 – Final Report of the NFP 42+ commissioned by the Swiss Federal Council” which was compiled and written by Georg Kreis and published in 2007.

By 1967, South Africa had constructed a reactor as part of a plan to produce plutonium, the SAFARI-2 located at Pelindaba. SAFARI-2 was part of a project to develop a reactor moderated by heavy water which would be fuelled by natural uranium and cooled using sodium. This link to developing heavy water for the creation of uranium, the same technology which had been utilised by the Nazis also with the help of Escher-Wyss, may explain why South Africans initially got Escher-Wyss involved. But by 1969, South Africa abandoned the heavy water reactor project at Pelindaba because it was draining resources from their uranium enrichment program that had first begun in 1967.

In 1970, Escher-Wyss were definitely deeply involved with nuclear technology, as seen in a record available in the Landesarchivs Baden-Württemberg. The record shows details of a public procurement process and contains information about award talks with specific companies involved in the procurement of nuclear technology and materials. The companies cited include: NUKEM; Uhde; Krantz; Preussag; Escher-Wyss; Siemens; Rheintal; Leybold; Lurgi; and the infamous Transnuklear.

The Swiss and South Africans had a close relationship through this period of history, when it was hardly easy for the brutal South African regime to find close allies. By 4 November 1977, the United Nations Security Council had enacted resolution 418 which imposed a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa, an embargo that wouldn’t be fully lifted until 1994.

Georg Kreis pointed out the following in his detailed assessment of the Hug report:

“The fact that the authorities assumed a laisse-faire attitude even after May 1978 comes to the fore in an exchange of letters between the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the DFMA in October/December 1978. As the study by Hug explicates, the Anti-Apartheid Movement of Switzerland pointed to German reports according to which Sulzer Escher-Wyss and a company called BBC had supplied parts for the South African uranium enrichment plant, and to repeated credits to ESCOM, which also included considerable contributions by Swiss banks. These assertions led to questions of whether the Federal Council – in light of fundamental support of the UN embargo, ought not to instigate the National Bank to stop authorising credits for ESCOM in the future.”

Swiss banks would help to fund the South African race to nukes and, by 1986, Sulzer Escher-Wyss were successfully producing special compressors for uranium enrichment.

The Founding of the World Economic Forum

In 1970, the young upstart, Klaus Schwab wrote to the European Commission and asked for help in setting up a “non-commercial think tank for European business leaders”. The European Commission would sponsor the event as well, sending French politician Raymond Barre to act as the forum’s “intellectual mentor”. Raymond Barre, who was at that time European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, would later go on to become French PM and would be accused of making anti-Semitic comments while in office.

So, in 1970, Schwab left Escher Wyss to organise a two-week business managerial conference. In 1971, the first meeting of the World Economic Forum – then called the European Management Symposium – convened in Davos, Switzerland. Around 450 participants from 31 countries would take part in Schwab’s first European Management Symposium, mostly made up of managers from various European companies, politicians, and US academics. The project was recorded as organised by Klaus Schwab and his secretary Hilde Stoll who, later the same year, would become Klaus Schwab’s wife.

Klaus’s European symposium was not an original idea. As writer Ganga Jey Aratnam stated quite coherently in 2018:

“Klaus Schwab’s “Spirit of Davos” was also the “Spirit of Harvard”. Not only had the business school advocated the idea of a symposium. Prominent Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith championed the affluent society as well as capitalism’s planning needs and the rapprochement of East and West.”

It was also true that, as Aratnam also pointed out, this was not the first time Davos had hosted such events. Between 1928 and 1931, the Davos University Conferences took place at the Hotel Belvédère, events which were co-founded by Albert Einstein and were only halted by the Great Depression and the threat of looming war.

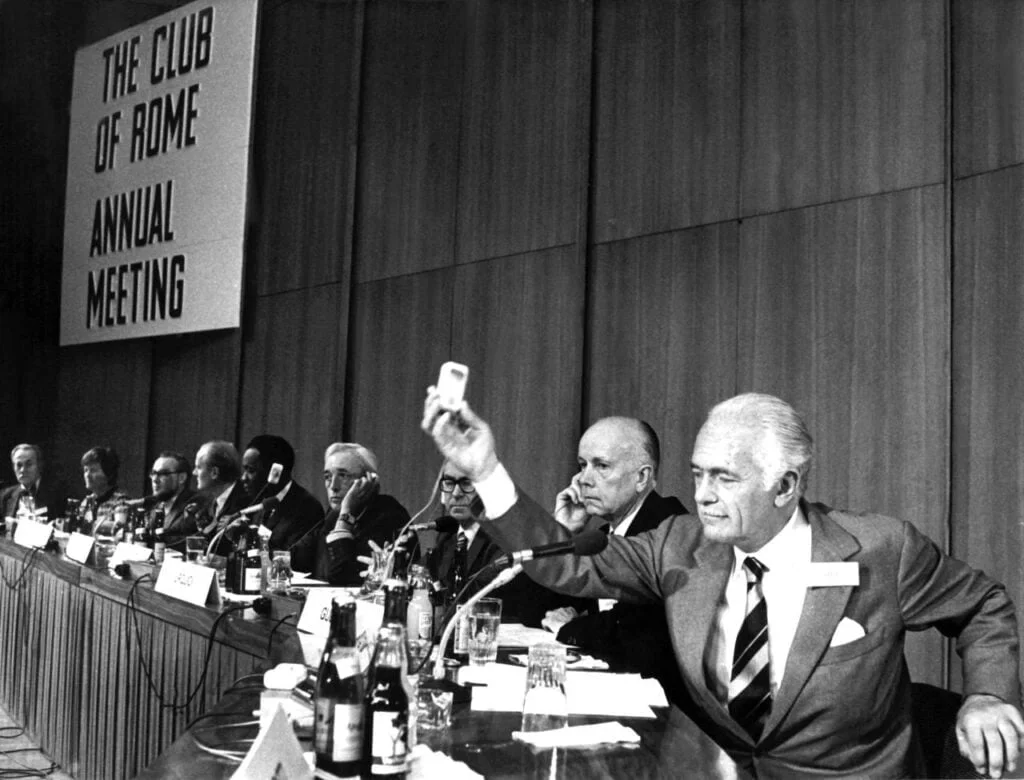

The Club of Rome and the WEF

The most influential group that spurred the creation of Klaus Schwab’s symposium was the Club of Rome, an influential think tank of the scientific and monied elite that mirrors the World Economic Forum in many ways, including in its promotion of a global governance model led by a technocratic elite. The Club had been founded in 1968 by Italian industrialist Aurelio Peccei and Scottish chemist Alexander King during a private meeting at a residence owned by the Rockefeller family in Bellagio, Italy.

Among its first accomplishments was a 1972 book entitled “The Limits to Growth” that largely focused on global overpopulation, warning that “if the world’s consumption patterns and population growth continued at the same high rates of the time, the earth would strike its limits within a century.” At the third meeting of the World Economic Forum in 1973, Peccei delivered a speech summarizing the book, which the World Economic Forum website remembers as having been the distinguishing event of this historical meeting. That same year, the Club of Rome would publish a report detailing an “adaptive” model for global governance that would divide the world into ten, inter-connected economic/political regions.

The Club of Rome was long controversial for its obsession with reducing the global population and many of its earlier policies, which critics described as influenced by eugenics and neo-Malthusian. However, in the Club’s infamous 1991 Book, The First Global Revolution, it was argued that such policies could gain popular support if the masses were able to link them with an existential fight against a common enemy.

To that effect, The First Global Revolution contains a passage entitled “The common enemy of humanity is Man”, which states the following:

“In searching for a common enemy against whom we can unite, we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming, water shortages, famine and the like, would fit the bill. In their totality and their interactions these phenomena do constitute a common threat which must be confronted by everyone together. But in designating these dangers as the enemy, we fall into the trap, which we have already warned readers about, namely mistaking symptoms for causes. All these dangers are caused by human intervention in natural processes, and it is only through changed attitudes and behaviour that they can be overcome. The real enemy then is humanity itself.”

In the years since, the elite that populate the Club of Rome and the World Economic Forum have frequently argued that population control methods are essential to protecting the environment. It is thus unsurprising that the World Economic Forum would similarly use the issues of climate and environment as a way to market otherwise unpopular policies, such as those of the Great Reset, as necessary.

The Past is Prologue

Since the founding of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab has become one of the most powerful people in the world and his Great Reset has made it more important than ever to scrutinize the man sitting on the globalist throne.

Given his prominent role in the far-reaching effort to transform every aspect of the existing order, Klaus Schwab’s history was difficult to research. When you start to dig into the history of a man like Schwab, who sits aloft other shadowy elite movers and shakers, you soon find lots of information has been hidden or removed. Klaus is somebody who wants to stay hidden in the shadowy corners of society and who will only allow the average person to see a well-presented construct of their chosen persona.

Is the real Klaus Schwab a kindly old uncle figure wishing to do good for humanity, or is he really the son of a Nazi collaborator who used slave labour and helped the Nazi efforts to obtain the first atomic bomb? Is Klaus the honest business manager who we should trust to create a fairer society and workplace for the common man, or is he the person who helped push Sulzer Escher-Wyss into a technological revolution that led to its role in the illegal creation of nuclear weapons for South Africa’s racist apartheid regime? The evidence I have looked at does not suggest a kindly man, but rather a member of a wealthy, well-connected family that has a history of helping create weapons of mass destruction for aggressive, racist governments.

As Klaus Schwab said in 2006 “Knowledge will soon be available everywhere – I call it the ‘googlisation’ of globalisation. It’s not what you know any more, it’s how you use it. You have to be a pace setter.” Klaus Schwab considers himself to be a pace setter and a top table player, and it must be said that his qualifications and experience are impressive. Yet, when it comes to practising what you preach, Klaus has been found out. One of the three biggest challenges on the priority list for the World Economic Forum is the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons, yet neither Klaus Schwab nor his father Eugen lived up to those same principles when they were in business. Quite the opposite.

In January, Klaus Schwab announced that 2021 is the year that the World Economic Forum and its allies must “rebuild trust” with the masses. However, if Schwab continues to hide his history and that of his father’s connections to the “National Socialist Model Company” that was Escher-Wyss during the 1930s and 1940s, then people will have good reason to distrust the underlying motivations of his overreaching, undemocratic Great Reset agenda.

In the case of the Schwabs, the evidence doesn’t point at simply poor business practices or some sort of misunderstanding. The story of the Schwab family instead reveals a habit of working with genocidal dictators for the base motives of profit and power. The Nazis and the South African apartheid regime are two of the worst examples of leadership in modern politics, yet the Schwabs obviously couldn’t or wouldn’t see that at the time.

In the case of Klaus Schwab himself, it appears that he has helped to launder relics of the Nazi era, i.e. its nuclear ambitions and its population control ambitions, so as to ensure the continuity of a deeper agenda. While serving in a leadership capacity at Sulzer Escher Wyss, the company sought to aid the nuclear ambitions of the South African regime, then the most Nazi adjacent government in the world, preserving Escher Wyss’ own Nazi era legacy. Then, through the World Economic Forum, Schwab has helped to rehabilitate eugenics-influenced population control policies during the post-World War II era, a time when the revelations of Nazi atrocities quickly brought the pseudo-science into great disrepute. Is there any reason to believe that Klaus Schwab, as he exists today, has changed in anyway? Or is he still the public face of a decades-long effort to ensure the survival of a very old agenda?

The last question that should be asked about the real motivations behind the actions of Herr Schwab, may be the most important for the future of humanity: Is Klaus Schwab trying to create the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or is he trying to create the Fourth Reich?

Part 2:

Dr. Klaus Schwab or: How the CFR Taught Me to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

The World Economic Forum’s recorded history has been manufactured to appear as though the organisation was a strictly European creation, but this isn’t so. In fact, Klaus Schwab had an elite American political team working in the shadows that aided him in creating the European-based globalist organisation. If you have a decent knowledge of Klaus Schwab’s history, you will know that he attended Harvard in the 1960s where he would meet then-Professor Henry A. Kissinger, a man with whom Schwab would form a lifelong friendship. But, as with most information from the annals of the World Economic Forum’s history books, what you’ve been told is not the full story. In fact, Kissinger would recruit Schwab at the International seminar at Harvard, which had been funded by the US’ Central Intelligence Agency. Although this funding was exposed the year in which Klaus Schwab left Harvard, the connection has gone largely unnoticed – until now.

My research indicates that the World Economic Forum is not a European creation. In reality, it is instead an operation which emanates from the public policy grandees of the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixonian eras of American politics; all of whom had ties to the Council on Foreign Relations and the associated “Round Table” Movement, with a supporting role played by the Central Intelligence Agency.

There were three extremely powerful and influential men, Kissinger among them, who would lead Klaus Schwab towards their ultimate goal of complete American Empire-aligned global domination via the creation of social and economic policies. In addition, two of the men were at the core of manufacturing the ever present threat of global thermonuclear war. By examining these men through the wider context of the geopolitics of the period, I will show how their paths would cross and coalesce during the 1960s, how they recruited Klaus Schwab through a CIA-funded program, and how they were the real driving force behind the creation of the World Economic Forum.

Henry A. Kissinger

Heinz Alfred Kissinger was born in Bavaria, Germany, on 27 May 1923 to Paula and Louis Kissinger. The family had been one of many Jewish families fleeing the persecution in Germany to arrive in America in 1938. Kissinger would change his first name to Henry at 15 years old when arriving in America by way of a brief emigration to London. His family would initially settle in Upper Manhattan with the young Henry Kissinger attending George Washington High School. In 1942, Kissinger would enroll in the City College of New York, but, in early 1943, was drafted into the US Army. On 19 June 1943, Kissinger would become a naturalised US citizen. He would soon be assigned to the 84th Infantry Division where he would be recruited by the legendary Fritz Kraemer to work in the military intelligence unit of the division. Kraemer would fight along Kissinger during the Battle of the Bulge and would later become extremely influential in American politics during the postwar era, influencing future politicians such as Donald Rumsfeld. Henry Kissinger would describe Kraemer as being “the greatest single influence on my formative years”, in a New Yorker article entitled, The Myth of Henry Kissinger, written in 2020.

The writer of that article, Thomas Meaney, describes Kraemer as:

“A Nietzschean firebrand to the point of self-parody—he wore a monocle in his good eye to make his weak eye work harder—Kraemer claimed to have spent the late Weimar years fighting both Communists and Nazi Brown Shirts in the streets. He had doctorates in political science and international law, and pursued a promising career at the League of Nations before fleeing to the US in 1939. He warned Kissinger not to emulate “cleverling” intellectuals and their bloodless cost-benefit analyses. Believing Kissinger to be “musically attuned to history,” he told him, “Only if you do not ‘calculate’ will you really have the freedom which distinguishes you from the little people.””

During World War II, whilst Kissinger was serving in the U.S. Counter-Intelligence Corps, he would be promoted to the rank of sergeant and would go on to serve in the Military Intelligence Reserve for many years after peace was declared. During that period, Kissinger would take charge of a team hunting down Gestapo officers and other Nazi officials who had been labeled as “saboteurs”. After the war, in 1946, Kissinger would be reassigned to teach at the European Command Intelligence School, a position he would continue to work in as a civilian after officially leaving the army.

In 1950, Kissinger would graduate from Harvard with a degree in political science where he would study under William Yandell Elliott, who would eventually be a political advisor to six US presidents and would also serve as a mentor to Zbigniew Brzezinski and Pierre Trudeau, among others. Yandell Elliott, along with many of his star pupils, would serve as the key connectors between the American national security establishment and the British “Round Table” movement, embodied by organisations such as Chatham House in the UK and the Council on Foreign Relations in the United States. They would also seek to impose global power structures shared by Big Business, the political elite and academia. Kissinger would continue to study at Harvard, gaining his MA and PhD degrees at the prestigious university, but he was also already trying to forge a career path in intelligence, reportedly seeking recruitment as an FBI spy during this period.

In 1951, Kissinger would be employed as a consultant for the Army’s Operations Research Office, where he would be trained in various forms of psychological warfare. This awareness of psyops was reflected in his doctoral work during the period. His work on the Congress of Vienna and its consequences invoked thermonuclear weapons as its opening gambit, which also made an otherwise dull piece of work a little more interesting. By 1954, Kissinger was hoping to become a junior professor at Harvard but, instead, the dean of Harvard at the time, McGeorge Bundy – another pupil of William Yandell Elliott, recommended Kissinger to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). At the CFR, Kissinger would start managing a study group on nuclear weapons. From 1956 to 1958, Kissinger also became the Director of Special Studies for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund (David Rockefeller was vice-president of the CFR during this period), as well as going on to direct multiple panels to produce reports on national defense, which would gain international attention. In 1957, Kissinger would seal his place as a leading Establishment figure on thermonuclear war after publishing, Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy, a book published for the Council on Foreign Relations by Harper & Brothers.

In December of 1966, The Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs, John M Leddy, announced the formation of a 22-man panel of advisors to help “shape European policy”. The five most prominent actors of this panel of advisors included: Henry A Kissinger representing Harvard, Robert Osgood of the Washington Center of Foreign Policy Research (funded by Ford, Rockefeller and Carnegie money), Melvin Conant of Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Warner R Schilling of Columbia University, and Raymond Vernon who was also of Harvard. The other people on the panel included four members of the Council on Foreign Relations, Shepard Stone of the Ford Foundation, with the rest being a mix of representatives from leading American universities. The forming of this panel could be considered the laying of the proverbial foundation stone marking the American branch of the “Round Table” establishment’s intent to create an organisation such as the World Economic Forum, whereby Anglo-American imperialists would mold European policies as they saw fit.

Post-war Europe was at a vital stage of its development and the powerful American Empire was beginning to see opportunities in the rebirth of Europe and the emerging identity of its younger generation. In late December of 1966, Kissinger would be one of the twenty-nine “American authorities on Germany” to sign a statement declaring that “recent state elections in West Germany do not indicate a rebirth of Nazism”. The document, also signed by the likes of Dwight Eisenhower, was meant to signal that Europe was starting afresh and was meant to begin putting the horrors of European wars in the past. Some of the people involved in creating the aforementioned document were those who had already been externally influencing European policy from abroad. Notably, one of the signatures alongside Kissinger and Eisenhower was Prof. Hans J Morgenthau who was also representing the Council on Foreign Relations at the time. Morgenthau had famously written a paper entitled, Scientific Man versus Power Politics, and argued against an “overreliance on science and technology as solutions to political and social problems”.

In February 1967, Henry Kissinger would target European policy making as having been the reason for a century of war and political turmoil on the continent. In a piece entitled, Fuller Investigation, printed in the New York Times, Kissinger would state that a work by Raymond Aron, Peace and War. A Theory of International Relations, had remedied some of these issues.

In this article, Kissinger would write:

“In the United States the national style is pragmatic; the tradition until World War II was largely isolationist; the approach to peace and war tended to be absolute and legalistic. American writing on foreign policy has generally tended to fall into three categories: analyses of specific cases or historical episodes, exhortations justifying or resisting greater participation in international affairs, and investigations of the legal bases of world order.”

It was clear that Prof Henry A Kissinger had identified American involvement in European policy creation as being vital in the future peace and stability of the world. At this time, Kissinger was based at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Here, the future founder of the World Economic Forum, a young Klaus Schwab, would catch the eye of Henry A Kissinger.

Kissinger was the executive director of the International seminar, which Schwab often mentions when recollecting his time spent at Harvard. On 16 April 1967, it would be reported that various Harvard programs had been receiving funding from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). This included $135,000 of funding for Henry Kissinger’s International Seminar, funding which Kissinger claimed he was unaware had come from the US intelligence agency. The CIA’s involvement in funding Kissinger’s international seminar was exposed in a report by Humphrey Doermann, the assistant to Franklin L Ford, who was dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science. Humphrey Doermann’s report, written in 1967, only centred on the CIA funding from between 1961 to 1966, but Kissinger’s International seminar, which had received the most funding out of all the CIA-funded Harvard programs, would still run through 1967. Klaus Schwab arrived at Harvard in 1965.

On 15 April 1967, The Harvard Crimson would publish an article, attributed to no author, concerning Doermann’s report that stated, “There were no strings attached to the aid, so the government could not directly influence research or prevent its results from being published.” The dismissive article, entitled, CIA Financial Links, nonchalantly closes out by stating,”In any case, were the University to refuse to accept CIA research grants, the shadowy agency would have little trouble channeling its offers through another agrecy.” (agrecy being a pun meaning a form of intelligence).

The evidence points to Klaus Schwab having been recruited by Kissinger into his circle of “Round Table” imperialists via a CIA funded program at Harvard University. In addition, the year he graduated would also be the year in which it was revealed to have been a CIA-funded program. This CIA-funded seminar would introduce Schwab to the extremely well-connected American policy-makers who would help him create what would become the most powerful European public policy institute, the World Economic Forum.

By 1969, Kissinger would be sitting as the head of the US National Security Council, of which the sitting president, Richard Nixon would “enhance the importance of” during his administration. Kissinger was Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs between 2 December 1968 to 3 November 1975, serving concurrently as Richard Nixon’s Secretary of State from 22 September 1973. Kissinger would dominate the making of US foreign policy during the Nixon era and the system he would bring to the National Security Council would seek to combine features of the systems previously implemented by Eisenhower and Johnson.

Henry Kissinger, who had been one of the people to manufacture tensions between thermonuclear powers over the previous two decades, was now to act as “peacemaker” during the Nixon period. He would turn his focus to the European stand-off and would seek to relax the tensions between the West and Russia. He negotiated the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (culminating in the SALT I treaty) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. Kissinger was attempting to rebrand himself as a trusted statesman and diplomat.

In the second term of President Richard Nixon’s administration, their attention would turn to relations with Western Europe. Richard Nixon would describe 1973 as being the “Year of Europe”. The United States’ focus would be on supporting the states of the European Economic Community (EEC) which had become economic rivals to the US by the early 1970s. Kissinger grasped the “Year of Europe” concept and pushed an agenda, not only of economic reform, but also arguing to strengthen and revitalise what he considered to be the “decaying force”, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Throughout this period, Kissinger would also promote global governance.

Years later, Henry Kissinger would make the opening address of the World Economic Forum’s 1980 conference, telling the elites at Davos: “For the first time in history, foreign policy is truly global”.

John K. Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith (often referred to as Ken Galbraith) was a Canadian-American economist, diplomat, public policy maker, and Harvard intellectual. His impact on American history is extraordinary and the consequences of his actions in the late 1960s alone are still being felt around the world today. In September 1934, Galbraith would initially join the faculty at Harvard University as an instructor with a salary of $2,400 per year. In 1935, he would be appointed a tutor at John Winthrop House (commonly known as Winthrop House) which is one of twelve undergraduate residential houses at Harvard University. In that same year, one of his first students would be Joseph P. Kennedy Jr, with John F. Kennedy arriving two years later, in 1937. Soon after, the Canadian Galbraith would become naturalised as a US citizen on 14 September 1937. Three days later, he would marry his partner, Catherine Merriam Atwater, a woman who, a few years before, had been studying at the University of Munich. There, she had lived in the same rooming house-dormitory as Unity Mitford, whose boyfriend was Adolf Hitler. After marrying, Galbraith would travel extensively in Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, Italy, France, but also Germany. Galbraith had been due to spend a year as a research fellow at the University of Cambridge under famed economist John Maynard Keynes, but Keynes’ sudden heart attack would see Galbraith’s new wife persuade him to study in Germany instead. During the summer of 1938, Galbraith would study German land policies under Hitler’s government.

The following year, Galbraith found himself involved in what was termed at the time, “the Walsh-Sweezy affair” – a US national scandal involving two radical instructors who had been terminated from Harvard. Galbraith’s connections with the affair would result in his appointment at Harvard not being renewed.

Galbraith would take a demotion to work at Princeton, where he would soon after accept an invitation from the National Resource Planning Board to be part of a review panel into New Deal spending and employment programs. It is this project which would see him first meet Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1940, as France fell to Nazi forces, Galbraith would join the staff of the National Defense Advisory Committee, at the request of FDR’s economic advisor, Lauchlin Curry. Although that committee would be swiftly dissolved, Galbraith soon found himself appointed to the Office of Price Administration (OPA), heading up the division tasked with price control. He would be dismissed from the OPA on 31 May 1943. Fortune Magazine had already been trying to headhunt Galbraith since as early as 1941, and would soon scoop him up to join their staff as a writer.

The biggest shift in focus for Galbraith happened in 1945, the day after the death of Roosevelt. Galbraith would leave New York for Washington, where he would be duly sent to London to assume a division directorship of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, tasked with evaluating the overall economic effects of the wartime bombing. By the time he had arrived at Flensburg, Germany had already formally surrendered to the Allied forces and Galbraith’s initial task would change. He would accompany George Ball and be part of the interrogation of Albert Speer. In this one move, Galbraith had gone from being a policy advisor dealing with statistics and projections concerned with pricing, to the co-interrogator of a high-ranking Nazi war criminal. Speer had been in various important positions during the war, including as the Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production, one of the key men behind the organisation, maintenance and arming of every part of the Nazi Wermacht.

Soon after, Galbraith would be sent to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to evaluate the effects of the bombing. In January 1946, John Kenneth Galbraith was involved in one of the defining moments of American economic history. He would take part in the American Economic Association meetings in Cleveland, where, alongside Edward Chamberlin of Harvard and Clarence Ayres of Texas, he would debate Frank Knight and other leading proponents of classical economics. This event marked the coming-out of Keynesian economics, which would come to dominate post-war America.

In February 1946, Galbraith would return to Washington, where he would be appointed director of the Office of Economic Security Policy. It is here, in September of 1946, where Galbraith was tasked with drafting a speech for the Secretary of State, William Byrnes, outlining American policy towards German reconstruction, democratisation, and eventual admission into the United Nations. Galbraith, who opposed the group of politicians at the time referred to as “the Cold Warriors”, would resign from his position in October of 1946, returning to Fortune Magazine. He would also be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom that same year. In 1947, Galbraith would co-found the organisation, Americans for Democratic Action, alongside others including Eleanor Roosevelt, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and Ronald Reagan. In 1948, Galbraith would return to Harvard as a lecturer in Agricultural Forestry and Land-Use Policy. Soon after, he would be installed as a Professor at Harvard.

By 1957, Galbraith was beginning to form a closer relationship with his former student John F. Kennedy, who was by then junior senator for Massachusetts. The following year, JFK would publicly declare Galbraith as the “Phileas Fogg of the academic world” after receiving a copy of Galbraith’s book, A Journey to Poland and Yugoslavia, where he examined socialist planning up close. It is also in 1958 where Galbraith published “The Affluent Society” to critical acclaim, where he coined terms such as “conventional wisdom” and the “dependence effect”. It is around this time when Galbraith became the Paul M. Warburg Chair in economics at Harvard. This is the same position he would hold when he would first be introduced to a young Klaus Schwab.

By 1960, John Kenneth Galbraith had become an economic advisor to the Kennedy campaign. After Kennedy was elected President, Galbraith began staffing the new administration, famously being the man who recommended Robert S. McNamara for Secretary of Defense. In 1961, Kennedy would name Galbraith as ambassador to India and, later in the year, Galbraith would travel to Vietnam, at the behest of the President, to give a second opinion on the Taylor-Rostow report. On Galbraith’s advice, Kennedy would begin to withdraw troops from Vietnam.

In 1963, Galbraith would return to the United States, refusing an offer from Kennedy to take up an ambassadorship in Moscow, so as to return to Harvard. On the day Kennedy was assassinated, Galbraith was in New York with the publisher of the Washington Post, Katharine Graham. Galbraith would go straight to Washington and would be the man who drafted the original version of the new President’s speech to the joint session of congress. The year following JFK’s assassination, Galbraith would return to Harvard to develop a famous and highly popular course in Social Science that he would go on to teach for the following decade. He would still retain his position as an advisor to President Johnson, but would spend the rest of the year writing his final academic journals exclusively in economics.

By 1965, Galbraith had become increasingly louder in his opposition to the war in Vietnam, writing speeches and letters to the President. This rift would persist between Galbraith and Johnson, with Galbraith finally assuming the presidency of Americans for Democratic Action and going on to launch a national campaign against the Vietnam War entitled, “Negotiations Now!” In 1967, the rift between Galbraith and Johnson would only become wider when Senator Eugene McCarthy was persuaded by Galbraith to run against Johnson in the coming primary elections. Robert F. Kennedy was also hoping to recruit Galbraith to his own campaign but, although Galbraith had formed a close bond with the late JFK, he had not been so keen on Robert F. Kennedy’s distinctive style.

By the late 1960s, John K. Galbraith and Henry A. Kissinger were both considered to be two of the foremost lecturers, authors and educators in America. They were also both grandees at Harvard, Galbraith as the Paul M. Warburg Professor of Economics, and Kissinger as a Professor of Government, and the two men were focused on the creation of foreign policy for both America and the emerging new Europe. It was announced on 20 March 1968 that Kissinger and Galbraith would be the first speakers of the spring session of what was referred to as the “Mandeville Lectures series”, due to take place at the University of California, San Diego. Galbraith’s speech would be entitled, “Foreign Policy: The Cool Dissent”, whilst Kissinger’s speech was called “America and Europe: A New Relationship”.

Kissinger would introduce Klaus Schwab to John Kenneth Galbraith at Harvard and, as the 1960’s came to a close, Galbraith would help Schwab make the World Economic Forum a reality. Galbraith would fly over to Europe, along with Herman Kahn, to help Schwab convince the European elite to back the project. At the first European Management Symposium/Forum (the original name/s of the WEF), John Kenneth Galbraith would be the keynote speaker.

Herman Kahn

Herman Kahn was born in Bayonne, New Jersey on 15 February 1922 to Yetta and Abraham Kahn. He was brought up in the Bronx with a Jewish upbringing, but would later become atheistic in his beliefs. Throughout the 1950s, Khan would write various reports at the Hudson Institute on the concept and practicality of nuclear deterrence, which would subsequently become official military policy. He would also compile reports for official hearings, such as the Subcommittee on Radiation. It is in the primordial hysteria of the earliest years of the Cold War where Kahn would be given the intellectual, and some may say ethical and moral, space to “think the unthinkable”. Khan would apply game theory – the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions among rational agents – to wargame potential scenarios and outcomes concerning thermonuclear war.

In 1960, Kahn would publish, The Nature and Feasibility of War and Deterrence, which studied the risks and subsequent impact of a thermonuclear war. The Rand Corporation sums up the kinds of deterrents discussed in Kahn’s work as: the deterrence of a direct attack, the use of strategic threats to deter an enemy from engaging in very provocative acts other than a direct attack on the United States, and, lastly, the acts that are deterred because the potential aggressor is afraid that the defender or others will take limited actions, military or non-military, to make the aggression unprofitable.

The following year, Princeton University Press would first publish Herman Kahn’s seminal work, On Thermonuclear War. This book would have an enormous impact on the near and distant future of global politics and would drive American Establishment politicians to create foreign policy specifically designed to counter the potential worst case thermonuclear scenario. On the release of Kahn’s terrifying work, the Israeli-American sociologist and “communitarian”, Amitai Etzioni, would be quoted as saying, “Kahn does for nuclear arms what free-love advocates did for sex: he speaks candidly of acts about which others whisper behind closed doors”.

Khan’s complex theories have often been erroneously paraphrased, with most of his work being impossible to sum up in just a sentence or two, and this is emblematic of his ideas concerning thermonuclear war. Kahn’s research team were studying a multitude of different scenarios, a constantly evolving, dynamic, multipolar world, and many unknowns.

On Thermonuclear War had an instant and lasting impact, not only on geopolitics, but also on culture, expressed within a few years by a very famous movie. 1964 saw the release of the Stanley Kubrick classic, Dr Strangelove, and from the moment of its release, and ever since, Khan has been referred to as the real Dr. Strangelove. When quizzed about the comparison, Khan would tell Newsweek, “Kubrick is a friend of mine. He told me Dr. Strangelove wasn’t supposed to be me.” But others would point out the many affinities between Stanley Kubrick’s classic character and the real life Herman Kahn.

In an essay written for the Council on Foreign Relations in July 1966, entitled, Our Alternatives in Europe, Kahn states:

“Existing U.S. policy has generally been directed to the political and economic as well as the military integration or unification of Western Europe as a means to European security. Some have seen unification as a step toward the political unity of the West as a whole, or even of the world. Thus, the achievement of some more qualified form of integration or federation of Europe, and of Europe with America, has also been held to be an intrinsically desirable goal, especially as national rivalries in Europe have been seen as a fundamentally disruptive force in modern history; hence their suppression, or accommodation in a larger political framework, is indispensable to the future stability of the world.”

This statement suggests that the preferred solution for future European/American relations would be the creation of a European union. Even more preferable to Kahn was the idea of creating a unified American and European superstate.

In 1967, Herman Kahn would write one of the most important futurist works of the 20th century, The Year 2000: A Framework for Speculation on the Next Thirty-Three Years. In this book, co-authored by Anthony J Wiener, Khan and company predicted where we would be technologically at the end of the millennium. But there was another document released soon after Kahn’s The Year 2000, which had been written simultaneously. That document entitled, Ancillary Pilot Study for the Educational Policy Research Program: Final Report, was to map out how to achieve the future society Kahn’s work in The Year 2000 had envisaged.

Under a section titled “Special Educational Needs of Decision-Makers”, the paper states: “The desirability of explicitly educated decision-makers so that they are better able, in effect, to plan the destiny of the nation, or to carry out the plans formulated through a more democratic process, should be very seriously considered. One facet of this procedure would be the creation of a shared set of concepts, shared language, shared analogies, shared references…” He goes on to state in the same section that: “Universal re-teaching in the spirit of the humanistic tradition of Europe – at least for its comprehensive leadership group – might be useful in many ways.”

When you study the previously mentioned rhetoric and decipher what it means, in this document Herman Kahn suggests subverting democracy by training only a certain group in society as potential leaders, with those pre-selected few who are groomed for power being able to define what our shared values as a society should be. Maybe Herman Kahn would agree with the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Leader scheme, which is the exact manifestation of his original suggestion.

In 1968, Herman Kahn would be asked by a reporter what they do at the Hudson Institute. He would say, “We take God’s view. The President’s view. Big. Aerial. Global. Galactic. Ethereal. Spatial. Overall. Megalomania is the standard occupational hazard.” This was reportedly followed by Herman Kahn rising out of his chair, pointing his finger towards the sky and suddenly shouting out: ‘Megalomania, zoom!’”

In 1970, Kahn would travel to Europe with Galbraith to support Klaus Schwab’s recruitment drive for the first European Management Symposium. In 1971, Kahn would be sitting centre stage to watch John Kenneth Galbraith’s keynote speech at the historic first session of the policy making organisation which would eventually become the World Economic Forum.

In 1972, the Club of Rome published “The Limits to Growth”, which cautioned that the needs of the global population would exceed available resources by the year 2000. Kahn spent much of his final decade arguing against this idea. In 1976, Khan would publish a more optimistic view of the future, The Next 200 Years, which claimed that the potentials of capitalism, science, technology, human reason, and self-discipline were boundless. The Next 200 Years would also dismiss pernicious Malthusian ideology by predicting that the planet’s resources set no limits to economic growth, but rather, human beings would “create such societies everywhere in the solar system and perhaps to the stars as well.”

Schwab’s Three Mentors

Kahn, Kissinger and Galbraith had become three of the most influential people in America with regards to thermonuclear deterrence, foreign policy creation, and public policy making, respectively. Most of the focus throughout these men’s career had been on Europe and the Cold War. However, their varying roles in other important events of the period all have the potential to easily distract researchers from other more subversive and well hidden events.